Whatever Happened to Ambisonics?

Originally published in AudioMedia

Magazine, November 1991.

New: read comments

on this article in the form of a dialog between Richard Elen and noted

electronic music composer/performer Wendy Carlos, by kind permission of s2n

magazine.

The Ambisonic surround sound

system was developed in Britain during the 1970s, hard on the heels of the

so-called 'quadraphonic' techniques--and became tarred with the same brush.

For a number of reasons, more political than technical, it has up to now only

received limited acceptance in the consumer and professional audio market

places. But now all that is changing. Major interest from Japanese hi-fi manufacturers,

and the current interest in encode-only stereo enhancement are bringing the

system back into the limelight. But according to Richard Elen who has

been working with the system for over 15 years, it never went away.

"In nature, sounds come from all

around our ears. Reproduced sounds come from only a few loudspeakers. Directional

distortion results whenever our ears can hear the difference. As other distortions

in the audio chain have been progressively lessened, so directional distortion

has become more noticeable.

"The earliest widely used attempt

to mitigate directional distortion is stereo, which however gives a directional

illusion only over a frontal sound stage. The Ambisonic technology is the culmination

of over two decades of systematic research into how directional distortion can

be reduced as much as possible using any given number of audio channels and

loudspeakers.

"Just as the accurate reproduction

of performed music is the crucial test of audio fidelity, so the ability to

reproduce correctly the directionality of natural sounds is the crucial test

of a surround sound system. Unless it can do this, there will not be the correct

disposition of indirect sound which provides the acoustic ambience of the performance

and gives the position-dependent labelling of direct sounds by their wall reflections,

which is an important aspect of the appreciation of music. "If a system can

cope with this difficult task, it should go without saying that it can easily

deal with the relatively simple problems of synthetic source material. A system

of surround sound which is able to reproduce the directionality of indirect

reverberant sounds, as well as of direct sources, is termed 'Ambisonic'"

--NRDC Ambisonics brochure, 1979.

Ambisonics was the brainchild of

a small group of British academics, notably Michael Gerzon

of the Mathematical Institute in Oxford, and Professor P B Fellgett of the University

of Reading. From the beginning, it was designed as a surround sound system that

would overcome the major problems of the so-called 'quadraphonic' systems that

were its predecessors -- the main one being that they simply didn't work very

well. Research rapidly indicated, however, that in addition to providing full

surround sound in an encode/decode environment (where the original recording

is encoded into a stereo/mono-compatible form for transmission and later decoded

by the listener into multiple speaker feeds), Ambisonics could also offer a

significant 'super stereo' capability without decoding. With current interest

in single-ended stereo enhancement techniques like RSS and QSound [see Audio

Media April and Aug/Sept 1991 respectively], it's interesting to note that Ambisonic

processing equipment has been used as a single-ended stereo enhancement device

by radio stations, now especially AM stereo stations in the States, for almost

a decade.

Ambisonics built on the astonishing

work on stereo recording and reproduction performed by Britain's early audio

genius, Alan Dower Blumlein. Blumlein was working on stereo recording and disc-cutting

in the Twenties, and as well as developing the stereo cutting system introduced

over 30 years later for microgroove stereo LPs, he also invented what is at

once the simplest and most accurate of all stereo recording systems: M-S coincident

pair recording.

At a time when Bell Laboratories

in the States were also investigating stereo, but with omnidirectional spaced

microphones (which left a hole in the middle that required a third, centre channel

to fill it in - a precursor of Dolby surround?), Blumlein realised that there

was more to the ear/brain combination's ability to position sound source in

space than merely the difference in level between the ears. The principle is

easily illustrated by considering a conventional mixing console panpot being

used to pan a mono signal between two speakers -- an illustration that indicates,

too, how little Blumlein's work is now remembered in the audio industry.

Panpotted Mono

Something we often forget when we mix

a multitrack tape to 'stereo' is that what we're doing really represents the spatial

localisation of sound sources very poorly. Where we place a track in the space

between the speakers is purely a matter of which speaker is louder than the other--that's

what a panpot does.

Just imagine that you're listening

to a sound that's centre-stage. It has equal levels on both channels, and your

meters will read identical values. But now move to the left and what happens?

The sound follows you to the left, because now there's more energy reaching

you from the left than the right. That's the main drawback of this system--because

it's not 'stereo' at all: it's 'panpotted mono'. Send all the signal to the

left speaker and it comes from the left. Send equal levels to both speakers

and it's in the middle--or is it?

The standard stereo listening position,

with the speakers at 60 degrees to each other. Further apart than this and stereo

begins to develop a 'hole in the middle.' Normal panpots operate with level

only, so the listener in this example hears the sound coming from the left,

because there is more level arriving from the left-hand speaker.

Now the panpot is central,

but the listener has moved to the left. The sound still appears to be coming

from the left, because there is still more level arriving from the left-hand

speaker.

Phase-Shift Panning

When we listen to sounds in real life,

they don't behave like that. The reason is that level between our two ears is

just one of the methods we use to localise sound sources in space. There are two

others--phase and the 'Haas Effect'. Some researchers think that they're at least

as important as level.

If a sound is off to one side, we

still hear it with both ears, but there is a difference between the signals

arriving at the two ears. Apart from differences in level (and high frequency

content for that matter), there's another factor: phase. The wavefronts from

the sound source don't reach the ears at exactly the same time, and we interpret

that phase difference as localisation information. It's a very impressive effect

if you try it yourself in the studio.

A simple method of experimenting

with phase-based localisation is to set up a pair of delay lines, one variable

and the other fixed. Send the same mono signal to both of them and pan the output

of one hard left and the other hard right. Make sure that only the delayed signal

is delivered to the output--none of the input signal should be heard--and that

the levels from both DDLs is identical (eg. by setting them up on your console

metering). Set the delay on the fixed DDL to, say, 100 milliseconds. Set up

the other delay to a basic length of 100ms too, but with a knob to vary the

delay equally above and below this figure--say 100ms +/-50ms. Now vary the delay

back and forth either side of the 100ms position and either side of the 100ms

position and you'll hear that, without changing the levels at all, you can create

a remarkable panning effect. You'll notice that at some settings, sounds can

even seem to go way beyond the speakers...

Switch your monitoring into mono

while you do this, by the way, and you'll hear a familiar sound--the 'swooshing'

effect of true 'tape phasing' or 'flanging'. This was how, using tape machine

record-play head delays instead of DDLs, George Chkiantz at Olympic Studios

produced the original sound of 'phasing' on the Small Faces hit, Itchycoo

Park--possibly its first controlled use (the effect had been used on the

soundtrack of a Fifties movie, The Big Hurt, but this was done by running

two identical copies of a piece of music together and changing the speed of

one of them to bring it into sync--a rather haphazard way of creating the effect).

Setup for phase-shift panning.

Use this in mono to obtain flanging.

Echoes And Delays

The third method of spatial localisation

used by the ear/brain combination is called the Haas Effect, after the man who

discovered it. The theory is simple: if we hear a sound directly, but we also

hear it at the same time indirectly, say bouncing off a wall, two signals arrive

at the ears. The direct sound arrives first, but the reflected sound turns up

just a little later. The brain rightly interprets that second arrival as a reflection

and doesn't confuse it with the true direction of the sound. We're talking here

of significant delays in the order of tens of milliseconds. Exactly what delay

you can hear will vary between people--try it with the same setup as that described

above, but set the delays to different values and listen without twiddling at

the same time--but you will notice how the delay is ignored as a localisation

cue when it becomes longer than a certain amount. This is why, if you ADT a sound

and split it hard left and right in a mix (a useful production technique), you

have to increase the level of the delayed sound to make it appear equally balanced

with the direct sound on the other channel: the extra level is needed to fool

the brain into thinking that the delayed sound is something different with its

own localisation.

Taking a signal, splitting

it and delaying one path, then positioning the two signals hard left and hard

right gives a useful effect. However, for the level on both sides to sound

the same, the delayed channel must be louder to overcome Haas Effect, which

is trying to tell you that the delayed sound is just an echo.

The Simple Secrets Of Stereo

'Stereo', in the sense of two transducers

picking up signals from two points close to each other, had been demonstrated

as early as 1881, when Clement Ader had relayed music from the Paris Opera via

phone lines to the Paris International Exhibition of Electricity (see Tony Askew's

'The Amazing Clement Ader', Studio Sound, September 1981, p.44). But this

was nearer to 'two channel mono' than true stereo.

Blumlein's approach, on the other

hand, utilised a pair of microphones at the same point -- a coincident pair.

One mic was an omnidirectional type, and thus picked up everything--in stereo

terms, it picked up left plus right (L+R). At right angles to it, but as physically

close to the omni as possible, was a second microphone, with a figure-of-eight

response, pointing to the left. A figure-of-eight polar diagram means that sound

waves hitting one side cause a positive displacement with respect to the other

side, and so the signal picked up is actually the difference between left and

right (L-R).

The Blumlein coincident pair--an

omni mic crossed with a figure-of-eight pointing left.

You'll notice that this 'stereo'

is a bit odd. Instead of a left channel and a right channel, you have a 'sum'

and a 'difference' channel. You can't listen to them directly: they have to

be decoded into the more usual left and right channels. This is done by a simple

matrix. The sum of the two channels gives you (L+R) + (L-R) = 2L --the left

channel. Meanwhile, subtract one signal from the other (or simply mix them together,

reversing the polarity of the difference signal) and you get (L+R) - (L-R) =

2R --the right channel. Interestingly, you can simulate this effect without

using a sum-and-difference technique. Just take two microphones with cardioid

polar diagram and cross their capsules horizontally at 90 degrees. The effect

is virtually identical to Blumlein's technique, and needs no matrix decoding.

Coincident-pair stereo is a remarkable

technique. It is perhaps the simplest microphone technique that approaches our

own hearing in its ability to reproduce spatial information. On speakers at

a true 60 degrees to each other (as stereo speakers are meant to be) the sound

has remarkable depth--it isn't just a straight line between the speakers--and

the image is also incredibly stable, sounding more or less the same wherever

you are between the speakers, unlike panpotted mono. On headphones you can actually

seem to hear things behind you and, occasionally, even above you. This is not

as unlikely as it sounds-- do we need ears in the back of our head to hear things

going on behind us? No, the front-back asymmetry of our ears changes the characteristics

of sounds heard from behind us as compared to those in front.

Three-Dimensional Stereo

Ambisonics is simply Blumlein's stereo

system, extended into three dimensions. Three? Yes, Ambisonics is capable of encoding

sound sources from any direction in space, including vertically. The technique

employed in an Ambisonic microphone is to use the equivalent of a single omnidirectional

capsule plus three figure-of-eight capsules: one pointing left-right, one front-back,

and the other up-down. In most Ambisonic microphones, such as the Calrec Soundfield

mic and its successors, these four polar diagrams are simulated by a tetrahedral

array of capsules. This has the benefit of also allowing them to be electronically

corrected for true coincidence -- because the closer together the capsules are,

the more accurate the localisation is, particularly at high frequency. This is

one of the reasons that the Soundfield microphones are excellent M-S stereo mics

as well as having their (somewhat under-exploited) surround sound benefits. A

soundfield microphone is just that--a device for capturing all the sounds in an

environment so that they can be stored in such a way as to make it possible to

regenerate in the listening environment the original pattern of sound waves falling

on the microphone.

The Soundfield Mic--an omni

crossed with three figure-of-eights at right-angles.

Soon after the development of the

Soundfield microphone, developments began to be made in the field of simulating

soundfields as well as simply capturing them. The result is that today there

are comprehensive mixing systems that allow individual multitrack signals to

be panpotted into an Ambisonic picture--an area we'll look at later in this

article.

If a 'traditional' Blumlein M-S

coincident pair gives you two signals which need to be decoded to derive the

left and right speaker feeds, it's fairly obvious that a three-dimensional Blumlein

system will give you more of the same. In fact, the 'studio format' for Ambisonics,

generally known as B-Format, is exactly this: a mono (sum) signal from the omnidirectional

component (Left + Right + Front + Back + Up + Down), known as the 'W' component,

plus three difference signals: Front - Back (known as the 'X' component), Left

- Right (the 'Y' component), and Up - Down (the 'Z' component). Notice that

only four channels are needed to encode not only surround information, but also

height (Ambisonics with height is generally called 'Periphony'--"sound around

the edge"). So why did the old 'Quad' systems need four channels to encode simple

horizontal surround?

Two Quadraphonic Fallacies

So-called 'Quadraphony' was a rather

unfortunate failed series of attempts to persuade people to buy twice as many

amplifiers and loudspeakers. Produced in the early Seventies when the technology

was really not up to it, the systems available offered various combinations of

problems with, occasionally, some interesting effects.

At the root of Quad's problems were

several misconceptions. The idea was to reproduce a soundfield--which of course

exists all around the listener--but the idea that this could be represented

by recording four channels and replaying them through four speakers at 90 degrees

to each other around the listener was simply incorrect. You can obtain some

impressive effects, but in terms of accuracy, the results are disappointing.

One reason is that stereo simply does not work with speakers at 90 degrees--

you get holes between them.

At the root of Quad was the idea

of using panpotted mono in two dimensions with four channels, and some of the

(so-called 'Discrete' or '4-4-4') systems did no more than this: utilising sum

and difference systems in the same way as they are used in FM stereo--with subcarriers

on vinyl discs! --to get the mono compatible sum signals in the normal groove

and the difference signals modulated on subcarriers. The listener without a

decoder simply heard the baseband signals--Left Front plus Left Rear on one

side and Right Front plus Right Rear on the other--and missed out on the difference

signals encoded on the high frequency subcarriers.

To offer stereo compatibility without

subcarriers, many of the several systems available attempted to matrix the original

four 'Discrete' channels down to two, using phase relationships to encode the

surround positions, and then somehow recover the original four signals in the

decoding process. These systems were often referred to as '4-2-4' systems--four

original signals, matrixed into two transmission channels, and then decoded

into the original four again. Unfortunately, this is mathematically impossible,

and '4-2-2.5' would have been a better name for them. Instead of a sound panned

around the room in a circle actually going around the room in a circle, it would

do something else. In one case it went around a shallow ellipse, with little

front-back definition. In another the front stage was fine but the rear was

a very odd shape, with centre-rear being in the centre of the listening area.

Quadraphony: discrete 4-channel

recording were distributed on 4-track tape, encoded as subcarriers on to disc,

or matrixed into 2-channel and decoded

The spatial inaccuracies of

the quad systems was one of their major shortcomings as these attempts to

pan a sound in a circle indlcate. Only UD-4 got close.

The solution to poor localisation

was a system called 'logic decoding'. The principle here was that if there was,

say, one sound source playing, the system could work out where it was supposed

to be and turn the other speakers down. That's fine as long as there's only

one thing going on. Of course, there seldom is.

The original

Quad systems died out, but two developments of them were left behind. One was

Dolby Surround, which is now widely used in the film industry. It owes a lot

to two of the commonest Quadraphonic systems, CBS's SQ and Sansui's QS systems.

As its heritage might suggest, it is excellent for impressive sound effects

and ambience but is not highly accurate in its representations of localisation

(it is not intended to be), and it is sometimes quite difficult to work with--logic

decoding means that when several widely-spaced sounds are present, the sound

stage tends to collapse as the logic decoding is rendered less effective by

the multiple sources.

A Working Matrix

Not everything that came out of Quad

developments was flawed, however. One subcarrier system--developed by Nippon Columbia

and called UD-4 (the 'UD' standing for 'Universal Discrete') -- successfully recreated

a circular locus in the listening environment. As a Quad system, however, it was

limited in its success.

The big challenge for Ambisonics

was how to get the four sum-and-difference signal components into a form that

was stereo- and mono-compatible, so that the system was able to interface successfully

with existing systems. This was the challenge that Quad had failed, both with

the expense and difficulty of subcarrier systems--with their special styli and

loss of subcarrier information due to record wear--and with the inability of

matrix systems to recover all the surround information successfully. The answer

was a phase encoding matrix that brought together work carried out by the Ambisonic

team, the BBC, and some of the original designers of the UD-4 system. The Ambisonic

team had developed a matrix called '45J', and the BBC were doing test transmissions

with 'Matrix H'. Adding a dash of UD-4, the UHJ system was born.

Multi-Channel Compatibility

UHJ is a unique hierarchical system

of encoding and decoding directional sound information within the Ambisonics technology.

Depending on the number of channels available, the system can carry more or less

information--but at all times, UHJ is fully stereo- and mono-compatible. In its

most basic form, 2-channel UHJ, horizontal (or 'planar') surround information

can be carried by normal stereo signal channels--CD, DAT, FM radio, or whatever.

Summing the two channels gives a highly compatible mono signal which in fact is

a more accurate representation of the two-channel version than summing a conventional

'panpotted mono' source. If a third channel is available, this can be used to

give improved localisation accuracy to the planar surround effect. The third channel

does not have to have full audio bandwidth for this purpose, leading to the possibility

of so-called '2.5-channel' systems. The third channel can be broadcast via FM

radio, for example, by means of phase-quadrature modulation. Adding a fourth channel

to the UHJ system allows the encoding of full surround sound with height, known

as Periphony.

The theoretical path from B-format

to the various stereo/mono-compatible UHJ variants. In fact many mixing applications

will go straight from multitrack to 2-channel UHJ at present.

Although there are some compromises

as far as accuracy of localisation is concerned in the 2-channel UHJ system,

it is currently the encoding method of choice. UHJ recordings can be transmitted

via all normal stereo channels and any of the normal media can be used with

no alteration. Compact Disc has the capability of carrying two additional audio

channels over and above the two used for stereo: these would be ideal for 4-channel

UHJ but have as yet to be used for this purpose (there are of course no players

with this capability at present either). [The emerging DVD standards may

allow for multichannel Ambisonic signals - for details of the most appropriate

proposals, see the Acoustic Renaissance

in Audio Web site -- RE, 11/96]

At Home With Ambisonics: The Decoder

A fundamental consideration at the very

beginning of Ambisonic development was the question of the listening environment.

Ambisonics was originally envisaged as a system in which the home listening room

acoustic could be 'overlaid' by an image of the original soundfield captured at

a live performance--typically a classical concert. One of the other problems of

Quadraphonics, with its four speakers at 90 degrees to each other, was that the

layout had to be exactly square, and the listener had to sit at the dead centre

of the square. Most readers, I am sure, have visited numerous friends who keep

their stereo loudspeakers in some very odd places--one channel behind the sofa

and the other on top of the bookcase, for example. It's hard enough to get people

to put two speakers in sensible places for stereo--what about four for surround

sound?

The solution was to design the Ambisonic

decoder in such a way that rather than each speaker receiving a single channel

feed destined for it from the beginning, as in Quad--where you had to place

the speakers at home in the same relative positions as they had been in the

studio control room--you instead positioned the speakers in 'sensible' places,

then told the decoder where they were. The 'layout control' on an Ambisonic

decoder, therefore, causes the decoder to output the correct speaker feeds for

the speaker positions you would like (or are obliged to have). One result of

this feature is that you can have your front speakers in a normal stereo position.

An extension

of this principle is the ability to design Ambisonic decoders for any number

of speakers. Four is the minimum for planar surround, and six for periphony,

but in a large environment such as a cinema, it may be a good idea to have a

dozen speakers or more. There is no theoretical limit to the number of speakers.

Similarly, there are few limits to speaker positions, either. Your four speakers

at home or in the control room can be placed in any rectangle, wide or narrow,

as long as the ratio of the sides doesn't exceed 2:1. And because Ambisonics

tries to recreate the original soundfield, speakers tend to work together and

thus smaller speakers are often more effective for Ambisonic replay--they give

more accurate localisation across the frequency range because the drivers are

closer together, and they tend to exhibit better bass response than when the

same speakers are used in stereo. A typical monitoring setup in a control room,

therefore, is to use the main speakers for checking the stereo and four nearfield

monitors connected to a decoder for Ambisonic monitoring. Most decoders have

a bypass facility too, which enables the input signal to be monitored on the

front pair of speakers only, so stereo and mono nearfield monitoring can also

be carried out.

Simplified block diagram of

a planar-surround Ambisonic decoder

So What Happened?

If Ambisonics is so wonderful, how come

we aren't all using it? The answer is a sad tale of bad luck and politics. The

original University-based inventors of Ambisonics were in no position financially

to develop the idea commercially. Luckily, there was an organisation that was

established to do exactly this: to help University inventions get out into the

wide world of industry and commerce. The National Research Development Corporation

had achieved some notable successes in this kind of activity, and the fledgling

Ambisonics was presented to them. They were interested.

The NRDC approach consisted of obtaining

and administering the patents associated with an invention, funding its development,

and then finding a licensee for the invention. The inventors would then earn

a royalty from the invention and the NRDC would recoup its investment. That

was the theory, and it worked quite well in some areas. The NRDC approach would

particularly suit you if you had, for example, developed a new way of making

some kind of plastic. The idea could be licensed exclusively to a chemical manufacturer,

and off you go. For some other types of invention, however, the NRDC approach

was disastrous--as the inventor of the Hovercraft would testify.

In hindsight, some might propose

that the NRDC was not the best organisation to handle Ambisonics. However, although

a lot of things didn't happen, and a number of apparently ill-advised things

did, it is difficult to see what other organisation would have got Ambisonics

off the ground. The system may have languished for a decade or so, but it is

quite possible that without the NRDC it wouldn't be here at all.

The problem was that while the NRDC

was set up perfectly to license an invention to one exclusive licensee--ideal

with that chemical process, for example--it was not in the slightest bit in

a position to promote a system whose success rested on as many companies as

possible becoming licensees. We can imagine that it would have failed equally

with an invention like Compact Disc, DAT, Dolby B, or even the humble Compact

Cassette. While the NRDC had the funding to go around selling ideas to individual

companies, the idea of mass marketing an invention like Ambisonics --holding

big press conferences, exhibiting at trade shows, making demonstration records,

and generally selling one thing to a lot of people-- was out of the question.

Ambisonics needed something more like product marketing and less like searching

quietly for an exclusive licensee. It is even possible that the NRDC's brief

simply didn't allow it to do the things that Ambisonics needed.

One by one, however, companies began

to pick up on the system: record companies like Nimbus--the longest and most

consistent licensee, with literally hundreds of CDs produced over the last 25

years, every one Ambisonically recorded with their equivalent of a Soundfield

microphone; hi-fi manufacturers; and professional audio manufacturers like Calrec,

who produced the first Soundfield microphone.

Ambisonics was originally designed

to reproduce sonic actuality as accurately as possible--an approach exemplified

by Nimbus Records, whose 'Natural Sound' is more an entire philosophy than simply

a method of recording and playback: surround sound handled as accurately as

possible is just one of the facets of the Nimbus approach. However, there were

plenty of people who wanted to do decidedly unnatural things with the process,

like mixing multitrack recordings Ambisonically.

The idea of Ambisonic panpots had

been included in the original theoretical work by Michael Gerzon, but it wasn't

until the early 1980s that practical pieces of studio equipment began to emerge--from

Audio & Design Recording--which enabled conventional multitrack recordings

to be mixed into an Ambisonic format. These units (now licensed to Cepiar) were--and

still are--very cost-effective, and several major artists began to use them,

but in the meantime, apart from Nimbus, very little was happening.

A chicken-and-egg situation developed

during the Seventies and early Eighties in which hardware manufacturers looked

at Ambisonics but put their projects on hold due to lack of software--they were

looking for more than a series of classical CDs, however good they were. Boots

Audio, for example, were poised to launch a complete Ambisonic microsystem--

but changed their minds. Meanwhile, many people on the record side were unwilling

to make Ambisonic recordings because nobody could decode them.

This situation should never have

arisen, and it could have been short-circuited by two things, had they been

better known. The first was that Ambisonically-recorded albums sounded a lot

better than regular stereo, even if you didn't have a decoder. For example,

Digital Audio magazine in 1986 reviewed one of the first mainstream Ambisonically-mixed

CDs-- Stereotomy, by Alan Parsons--with comments like, "Studio pop production

doesn't get any better... a winner in the sound quality stakes. Sounds emerge

from everywhere, clear and clean. The opening of track 3... completely fooled

my dog into thinking a car had driven up the driveway. The only track in which

Ambisonics was not used... [was at] lower volume, more distant." It was worth

making Ambisonic records, even if nobody ever decoded them. And secondly, as

manufacturers like Minim and Troy Ambisonic (a maker of in-car Ambisonic systems)

quickly discovered, decoders could offer a 'super stereo' mode which would dramatically

enhance existing stereo recordings played through the decoder, by extracting

surround information and using it to create impressive localisation and 'wrap

around' effects.

And the strategy of trying to persuade

record companies to endorse Ambisonics and use it on all their albums--a similar

approach to that used by the failed Quad systems--really put the companies off.

Anything that smacks of double inventory is likely to do that. And besides,

not only was there no need to ask record companies to commit to Ambisonics;

you didn't need to ask them at all, any more than if you wanted to use a particular

make of digital reverb on your album. The decision was made in the studio by

the producer, not by someone at the record company. It was only very late in

the day that direct approaches began to be made to producers and studio personnel,

and then NRDC fell foul of the next problem -- the government that created it.

It's a known fact that Margaret

Thatcher's government really didn't like the idea of the NRDC. Their view was

that British inventions should stand or fall on their ability to attract industry

backing on their own, and that a "quango" -- a quasi non-governmental organisation

-- shouldn't do it for them. But rather than admit this, the course taken was

to restrict the NRDC and prevent it doing its job properly, so as to demonstrate

how such organisations were a Bad Thing--a technique which was also attempted

with the British Health Service. The NRDC was bound together with the National

Enterprise Board--who at the time used most of their budget to fund British

Leyland--to form a fictitious entity called the 'British Technology Group'.

Not too long after this, despite

highly competent NRDC people in charge of the Ambisonic project--as was the

case all along, it is important to point out-- virtually everything that was

being done, stopped being done. At the time, a member of staff privately suggested

to me that one of the main problems was that nobody knew how much funding they'd

have next month, so the idea of planning anything like a long-term marketing

plan for Ambisonics was completely out of the question. The system became moribund,

with a few exceptions: Nimbus Records; a few other enterprising record companies

like Brendan Hearne's York Ambisonic; parts of the BBC quietly doing drama and

concert recordings with Soundfield mics; EMI Music's KPM

Production Music Library; and manufacturers like Calrec, Audio & Design,

and Minim.

Eventually, the NRDC saw a way out

of the situation, simply by doing what they were best at--namely locating a

single, exclusive licensee and letting them take responsibility for 'doing something'

with the mass of Ambisonic technology, which by now included nearly 400 patents.

Very soon there were three contenders for the privilege: Nimbus Records, Avesco

plc, and a Canadian group called Maple Technology. To the likes of you and me,

Nimbus, with two decades' experience of the system, were number one contenders;

and Avesco, a major British technology-based group with interests in high technology

audio and video, were second. None of us knew anything about Maple, so it was

a great surprise when they were awarded the licence. Then everything went quiet

again--for months. Absolutely nothing happened and eventually the licence was

terminated. Next, Avesco got it--and also proceeded to sit on the technology

for months. They disposed of their Troy Ambisonic subsidiary (a condition of

obtaining the licence, apparently!). After a long period of inactivity, they

too lost the licence.

Finally, the exclusive licence to

Ambisonics passed to Nimbus Records. One of the first activities of then Company

Secretary Stuart Garman--an avid music enthusiast and long-term supporter of

Ambisonics--was to present the system to major Japanese manufacturers looking

for a way to offer new, serious surround sound capabilities in their products.

A UHJ decoder will handle Dolby Surround-encoded material very impressively,

interestingly enough, (it is also possible to convert Dolby Surround material

to UHJ) and UHJ itself is an ideal audio format for future TV and disc formats

and Digital Audio Broadcasting. And a built-in 'super stereo' processing mode

ensures that any stereo recording will sound impressive, UHJ encoded or not.

First to pick up the technology

was Mitsubishi, for their 'Home Theatre System', a fully-integrated audio/video

component series. The decoder in the Mitsubishi DA-P7000 system was implemented

entirely in the digital domain, the first commercial product of its kind. Since

then, at least two other major hi-fi manufacturers (Onkyo and Meridian) have

gone into development with the system and more announcements are expected shortly.

[These units are apparently still in their respective catalogues -- RE, 11/96]

Meanwhile, on the software front,

Collins Classics, at the time an increasingly important classical label, announced

their intention to record all their albums Ambisonically--not in the Nimbus

way with a single microphone array, but using multitrack digital recorders and

Ambisonic mixing equipment. The announcement followed a series of experiments

with the technology, including recordings of Vaughan Williams symphonies with

Sir Neville Marriner. Ambisonics, at last, was getting the attention it deserved.

Using Ambisonics

Applications for Ambisonics fall into

three main categories: natural sound recording with a single Soundfield-type microphone;

mixdown of conventional multitrack recordings; and stereo spatial enhancement.

There are also combinations of these categories--for example, a multitrack recording

might well use a Soundfield mic, and any Ambisonic recording will exhibit spatial

enhancement effects.

Natural Sound Recording

The technique here is simply to use

a 'Soundfield' type microphone and appropriate encoder. Several types of microphone

are available, notably the AMS-Calrec Soundfield mic and its Soundfield Research

successors, and it is even possible to create one with discrete microphone units--

Dr Jonathan Halliday, resident technical genius at Nimbus, created a planar Ambisonic

microphone with a combination of Schoeps and B&K mics with a custom encoder.

The Soundfield microphone control unit includes a B-Format output and this can

be recorded on a 4-track recorder for later modification, or encoded on the spot

to 2-channel UHJ. Encoders are available from Minim Electronics (portable), AMS,

and Audio & Design/Cepiar. Encoders often also offer transcoding facilities

(see below). The microphone can be placed anywhere you would position a good stereo

microphone--in other words, somewhere that sounds good. The microphone control

units generally allow some degree of manipulation so as to correct inadvertent

rotation of the mic while suspending it, for example, or a device like the Pan-Rotate

unit can be employed (see below). The results are excellent.

Ambisonic Mixing

Multitrack recordings can be mixed

to UHJ in a number of ways, depending on the sophistication of the recording

and exactly what you want to be able to do. The simplest method is to use a

Transcoder. The Transcoder--such as that originally manufactured by Audio &

Design and now available from Cepiar-- takes two pairs of stereo signals in,

and gives a UHJ 2-channel signal out. As transcoding also uses part of the encoding

process used in converting B-Format to UHJ, many encoders often offer transcoding

facilities. The front panel controls are simple: width controls for front and

rear stages, and a power switch. Typically, two console stereo groups are designated

front and rear and fed into the front and rear stereo inputs of the device.

The position of a sound source in the stereo soundstage is transcoded into an

equivalent position in the Ambisonic picture. So, for example, if a track is

panned hard left in the front stage--corresponding to 60 degrees left of centre

front in stereo--this will be transcoded to the left edge of the front stage

in the Ambisonic soundfield. The width of the input soundstages can be varied

between 0 and 180 degrees for the front and 0 to 150 degrees for the rear (localisation

is not as stable beyond 150 degrees at the rear) This means that the front stage

can cover up to the whole front half of the Ambisonic circle and the rear stage

cover almost all of the back. The Transcoder can also be used to convert existing

discrete Quad 4-track recordings to UHJ, by setting the stage widths to 90 degrees.

Because of the nature of the transcoding

process, the Transcoder cannot generate B-Format. It is also difficult to pan

around the room, as the console panpots are limited to panning across the front

or rear stages. If dynamic effects are required, the Pan-Rotate unit

can be used. This takes a mono input (typically from post-fade channel out on

the console via the patchbay) and allows it to be positioned anywhere in the

planar Ambisonic soundfield. A continuously rotating panpot sets up the direction

of the sound, while another "radius vector" control enables the apparent distance

of the sound from the centre to be varied, from full positive, through zero

at the centre, to full negative (ie. panning across a diameter of the soundfield).

Each Pan-Rotate unit will handle up to eight mono inputs. There is a rotate

control which rotates the entire signal generated by the unit. Additional B-Format

inputs can come in either before or after the master rotate control, so that

units can be daisychained, and the B-Format output is usually fed to a Transcoder's

B-Format input for UHJ encoding. Typically, the Pan-Rotate unit is used for

mix elements which need to be moved during the course of the mix, while the

Transcoder is used for elements which remain in their positions. [It can

also be used to transfer 5.1 recordings into B-Format --RE, 11/96.]

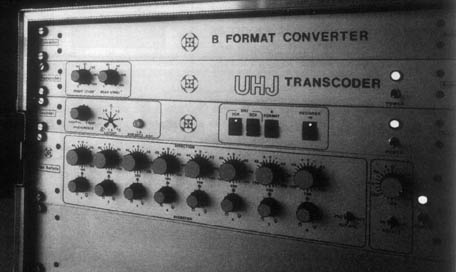

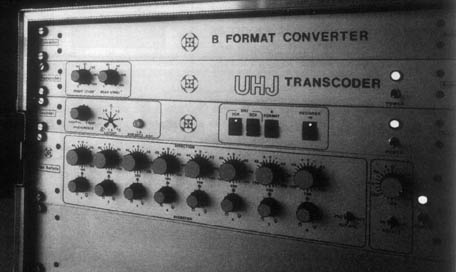

A more accurate, but seldom used,

unit is the B-Format Converter. This enables standard console panpots to be

used to generate B-Format signals. These can then be fed into a B-Format input

on a Pan-Rotate unit or straight into a Transcoder. The Converter is designed

to operate with constant-power console panpots but it operates entirely satisfactorily

with the compromise between constant-power and constant-voltage now generally

found on mixing consoles. An auxiliary send is derived postfade and set to the

same level as the fader output. This can be done by measurement or by ear and

provides the 'W' (mono) component of the B-Format signal. Then four groups are

fed into the unit. Selecting a pair of these groups (one odd, one even, as is

standard practice) and panning between them allows panning across one quadrant

(90 degrees) of the 360 degree Ambisonic soundstage. This unit is generally

used in combination with the other two.

Whatever mixing method you use,

experience indicates that if pan positions are determined while listening in

surround, you can then return to stereo monitoring and concentrate on that for

the rest of the mix: the surround will take care of itself. In fact, in general,

it is advisable to create the final balance while monitoring with the most basic

configuration the material is likely to be heard on. In other words, if most

of your listeners will hear the material in mono, monitor in mono as you do

your final balance. If most people will hear it in stereo, monitor in stereo.

The resulting surround balance will be fine.

Stereo Enhancement

Any Ambisonic recording is an 'enhanced

stereo' recording. As the standard information panel on many Ambisonic records

says, "This UHJ/Ambisonic recording will reproduce full surround sound when replayed

through an Ambisonic decoder; however, enhanced stereo and improved mono/stereo

compatibility will be experienced when replayed through normal audio equipment."

Ambisonics was designed originally

as an encode/decode system, in the same way as Dolby, and it is undeniable that

Ambisonic recordings are best experienced via a decoder with a multi-speaker

system. A typical stereo listening setup would be expected to have speakers

at 60 degrees for the front stage, and in its simplest form an Ambisonic decoder

just adds two speakers to the rear in the same configuration. When decoded,

a horizontal surround Ambisonic system can be used to localise a source anywhere

within a circle. Every position in the circle is represented by a unique combination

of phase and level, once again. In fact, in Ambisonics, the phase/level combinations

have been psychoacoustically set up to closely emulate the relationships actually

experienced in our hearing.

When the decoder is bypassed (or

missing), the rear signals are 'folded over' to the front speakers This means

that something at the far left or right edges of the circle will actually fall

outside the speakers in stereo, when the decoder is switched out and only the

standard stereo speakers are used. Signals in the rear soundstage additionally

have a more distant quality--when undecoded their level is reduced slightly

to enhance this effect--and generally appear behind the listener due to 'aural

decoding' (the brain attempts to localise the sound source correctly, based

on the phase and level information).

Ambisonics can therefore rightly

be considered as a 'stereo spatial enhancement system'. In fact, the results

of listening to 'undecoded' Ambisonic mixes are very impressive. Mono compatibility

is excellent and there are no 'forbidden positions' which don't work in mono.

The spatial effects experienced

with nondecoded Ambisonics are at least as impressive as those achieved with

some of the systems currently in vogue, but they are more stable and are very

independent of listener position--you can get the effect almost anywhere in

the room. There is little or no sound change caused by different spatial positions

and there is no appreciable 'phasiness'. The reproduction of spatial positions

is very accurate up to about 180 degrees--beyond that strong positions are heard,

but they are not as accurate as when the signal is decoded. However, the undecoded

results are highly satisfactory and rival those of other systems--but without

the expense or the shortcomings.

The mono/stereo compatibility of

Ambisonics means that a recording can be made which at the same time offers

mono listeners an exceptionally accurate balance; stereo listeners a stereo

that is much wider and more stable than conventional panpotted-mono, and is

less dependent on listener position; while listeners with a decoder can experience

a uniquely accurate full surround sound. In a world in which few people currently

have decoders, this 'future-proof' aspect of an Ambisonic recording, offering

full compatibility with existing systems, impressive stereo enhancement effects,

and with the ability for those same recordings to be decoded at a later date

into full surround, is very important.

Simple stereo enhancement can be

carried out by processing existing mixes through a Transcoder. This technique

is used by several AM stereo radio stations in the USA to make their stereo

signal sound more impressive. Simply feed the stereo signal into the front stage

inputs of the Transcoder and set the front stage width to maximum. The UHJ output

can be treated as stereo. You can try adding reverberation, with the reverb

returns being brought back to the rear stage inputs.

However, it is generally much more

impressive to use the Transcoder as described for basic Ambisonic mixing, feeding

groups into the unit and mixing with it rather than processing the balance afterwards.

In this case you are actually creating an Ambisonic recording, and if it isn't

too much trouble, it's worth listening to it via a decoder and four speakers

from time to time.

A Word About Mono

Two-channel UHJ Ambisonic recordings

actually offer better mono compatibility than panpotted mono recordings. But there

are other benefits, too. Particularly noticeable is the fact that Ambisonic recordings

are very robust. Because every position in the soundfield has a unique combination

of phase and level, the effect of azimuth errors is minimised. This is particularly

useful in environments where unstable stereo sources are summed into mono very

frequently--NAB cartridges still used by many radio stations being an excellent

example. The azimuth on these machines can wander dramatically during playback,

giving a watery, phasey sound for mono listeners. An Ambisonic recording, however,

will not suffer so much under the same conditions. The phasing effect is caused

by major parts of the stereo signal cancelling as they move past each other in

mono, because of variations in azimuth. However, as the parts of an Ambisonic

signal have different phase relationships, individual elements cancel at different

times under the same conditions. The result, instead of a phasey effect, is of

a subtle change of balance over time. This is seldom noticeable.